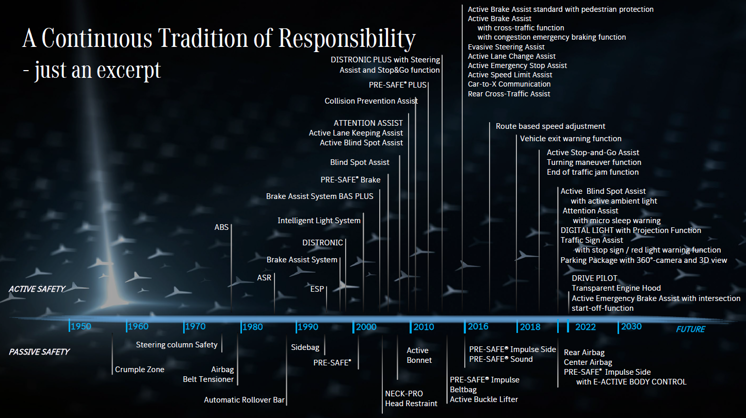

Pioneers of the car itself, Mercedes-Benz is similarly known for introducing the latest and greatest automotive technology and advancements, both in performance, but also more crucially, safety.

From the introduction of ABS and airbags in the 1970s to ESP and active cruise control in the 1990s, the 21st century has seen such an incredible amount of both passive and active safety systems introduced, it’s tricky to keep track of them all; with many of them from Mercedes. And next in line, for example, is fully automatic lane-change overtaking.

It used to be easy, explained Jochen Haab, Manager Field Validation, part of the team visiting from Mercedes-Benz Germany: “Traditionally, we used to showcase the latest developments in the most expensive S-Class model,” with the technology then dripping down to lower models over subsequent years. “But with the Moose test, we fitted it to the A Class… we made it standard across the range,” Haab referring to the infamous moment in 1997 when the A class rolled over during the moose/elk test, which swerves to avoid an accident, and expedited ESP’s introduction.

Since then, “ESP has saved as many as 2-3 million lives over the past 25 years,” he adds, stating technology now sweeps across the range of Mercedes, says Jochen, “from A-Class to Maybach… which our Z.” So the typical four-year model life-cycle with incremental updates has now been supplanted by the introduction of safety technology in whichever model is newest, with the current range of active safety being generation 4 and 5, with generation 6 due in the next CLA in 2025.

With the Mercedes-AMG C63 E just driven by DRIVEN, along with the GLC 300 and 43 Coupes, GLE 450d and AMG GLE 63 S, the GLS 450d and the new E-Class about to land, it’s been a very busy six months for Mercedes-Benz NZ, with new models, new technology and new safety.

A recap was in order, of not just the latest safety tech, but how Mercedes-Benz has both pioneered and pushed these developments of the decades; in the form of the Mercedes-Benz Intelligent Drive Insight day, held at Sandown Raceway, Victoria.

While the car itself has existed since 1886, also considered a Mercedes invention, as we covered in our CARology video, safety wasn’t really a considered factor until the 1950s, with the introduction of crumple zones and seat belts.

Mercedes has focused both on occupant and pedestrian safety, with things like a bonnet that raises in impacts to help minimise personal injury, and automatic emergency braking to either minimise or eliminate crashes into cars or people.

Split into five exercises, exercise 1 starts with possibly the most dangerous and harrowing: on a public road. Uncontrolled and unpredictable, Jochen drove us out onto the Princes Highway for a 30 minute loop demonstrating the everyday aspects of Mercedes’ safety tech… and hopefully none of the emergency ones. He double-clicks the cruise control cancel button to enable the Distronic cruise control system to read and automatically react to the speed signs, the E-Class sitting on the 100km/h signed limit.

With Jochen setting the following distance setting to the minimum, our speed adjusts to the car in front to leave a two-second gap, regardless of the speed, with the blind spot monitors flashing in the exterior mirrors as cars pass. As we exit the motorway, and Jochen is forced to manually operate the brake pedal as we approach an empty intersection with a red light; prompting Jochen to talk of a new development where the system will be able to recognise red lights at empty intersections in the distance and react accordingly.

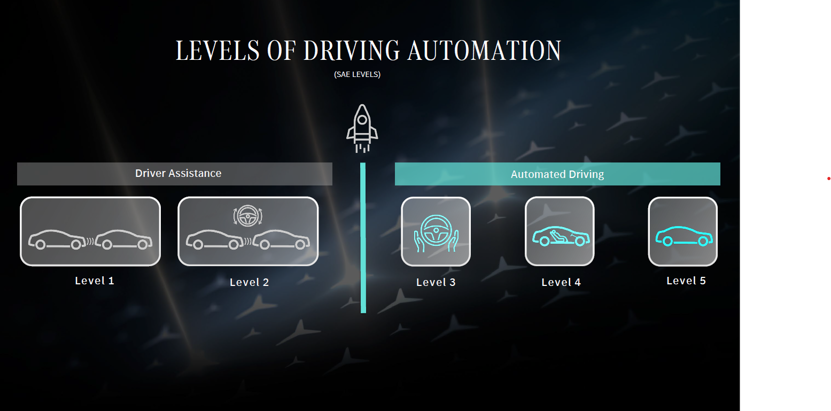

This has the potential to take it from Level 2 semi-autonomous driving, where the driver always maintains control and where we are at now, to Level 3, where the vehicle is both responsible from a function perspective, but also a liable one, with Jochen explaining with Level 3 Drive Pilot is currently only approved in Germany and the US states of California and Nevada.

“We compare Drive Pilot to the moon landing”, says Matthias Kaiser, emphasising its scale and scope of how it will change autonomous driving over the coming years. “Checking 2700 parameters via 10 sensors places around the car, it can also detect unexpected traffic situations, and independently cope with them by evasive manoeuvres within in the lane or braking.” Though the driver will always have override control and keep their hands on the wheel, Drive Pilot can provide control and intervention where needed, through active driving manoeuvres or safety intervention.

This will also enable things like fully automatic lane changing, where the car will approach a vehicle, and at speeds between 80-140km/h and where safe to do so, proceed with a lane-change overtake, and return to its original lane, without the driver’s input. While the country legalities are likely the biggest hurdle, the Level 3 technology does already exist to take not just responsibility, but legal liability in extreme cases – though Jochen didn’t comment on the challenges of New Zealand’s propensity to steadfastly drive in the fast lane.

Exercise 2 was a showcase of robots and how not to hit them with various moving obstacles doing their best to be hit. Mercedes has developed a range of walking and riding humanoid adult and child robots to simulate and help mitigate a range of potential accidents. Our course sets up on the large Sandown carpark, with a standard autonomous 60km/h emergency stop before hitting the back of a simulated (soft) car, effectively getting us warmed up.

But it’s more than that, with the car showing stages of safety, from warnings and alerts, through support and preparation (like seat-belt pre-tensioning, or an 80dB burst of white noise through the speakers to prepare human ears for the potentially hearing-damaging noise and pressure change of an impact) and then active intervention. It also works if a car’s brake lamps aren’t working, or at night, constantly assessing crash risk and avoidance.

Through various exercises a particularly aggressive robotic motorcyclist attempts to invoke road rage by pulling out in front of us, braking sharply, triggering our own automatic emergency braking, pulling us up to a stop merely centimetres from its rear tyres; then as the panic of an emergency stop subsides, a robotic child on a bicycle starts its own end-of-life strategy, pulling into the path of the Mercedes in various ways and directions, happily riding off again, totally oblivious and ignorant to the carnage that the car’s technology saved it from.

Time again, the Mercedes’ system either braked heavily, lightly, or even cuts power (when potentially pulling away from standstill and into the path of bicycle child), to avoid collisions, as our remote-controlled robotic hazards do their best to cause them. And in every case, allowing the pedestrian or cyclist to pass unimpeded and unharmed.

Exercise 3 was parking. And while Mercedes-Benz’s Parktronic and Park Assist has been around for near 20 years, it has undergone big improvements. The car is now always scanning for parking space, and simply needs the appropriate gear selected to enable it to automatically park itself: either parallel, or front or rear-in perpendicular parking.

Improvements to speed, doubling it from 2km/h to 4kmh, make a big difference, as does obstacle recognition – in our case, a mock child on a tricycle – and the ability to choose which parking space when few cars are present. Once the gear is selected, the car now switches between forward and reverse where required, along with turning the wheel at the perfect angle. Even a live human cyclist rides by to activate further safety aspects such as preventing opening a door into them.

Our fourth exercise takes to Sandown’s front straight, where we wind it up to 80km/h and barrel head first towards a dead-end of stopped cars, showcasing that even at high speeds, the automatic emergency braking gives the driver reassurance that even the worst, most inattentive driver has a chance at either minimising or avoiding a rear-end crash: also a reminder that in 10-20 years when most cars have this technology as standard, we will substantially reduce the number of simple front-to-rear crashes and fender-benders, which anyone in a built-up area or motorway commute will laud.

Our last exercise is easily the most fun, behind the wheel of a rear-wheel drive C-Class, with special plastic covers over the rear tyres, designed to mimic driving on ice, but also to intentionally slide and activate the ESP stability control. It works exactly as it says on the label, but after a full half-day or safety and restraint, the freedoms of an open track, no rear grip and the ability to slide a car around prove a few moments of relaxing relief.