We do our best to protect the private information stored on our multiple computers and digital devices from malicious hackers. But will we soon need to prioritise the security of the microprocessors in the family car, too?

It’s a concern that carmakers should be taking far more seriously, suggests one cybersecurity consultancy firm.

General manager of Aura InfoSec, Peter Bailey, says the next big frontier requiring robust digital legislation and protection will be the automotive industry.

When you think about it, even the lowliest entry-level hatchback is an incredibly complex beast.

Depending on its specifications, the modern passenger car has between 20 and 70 microprocessors on-board that control all sorts of aspects of in-car comfort and safety — from climate-control air conditioning to Bluetooth phone connections, emergency braking systems and adaptive cruise control.

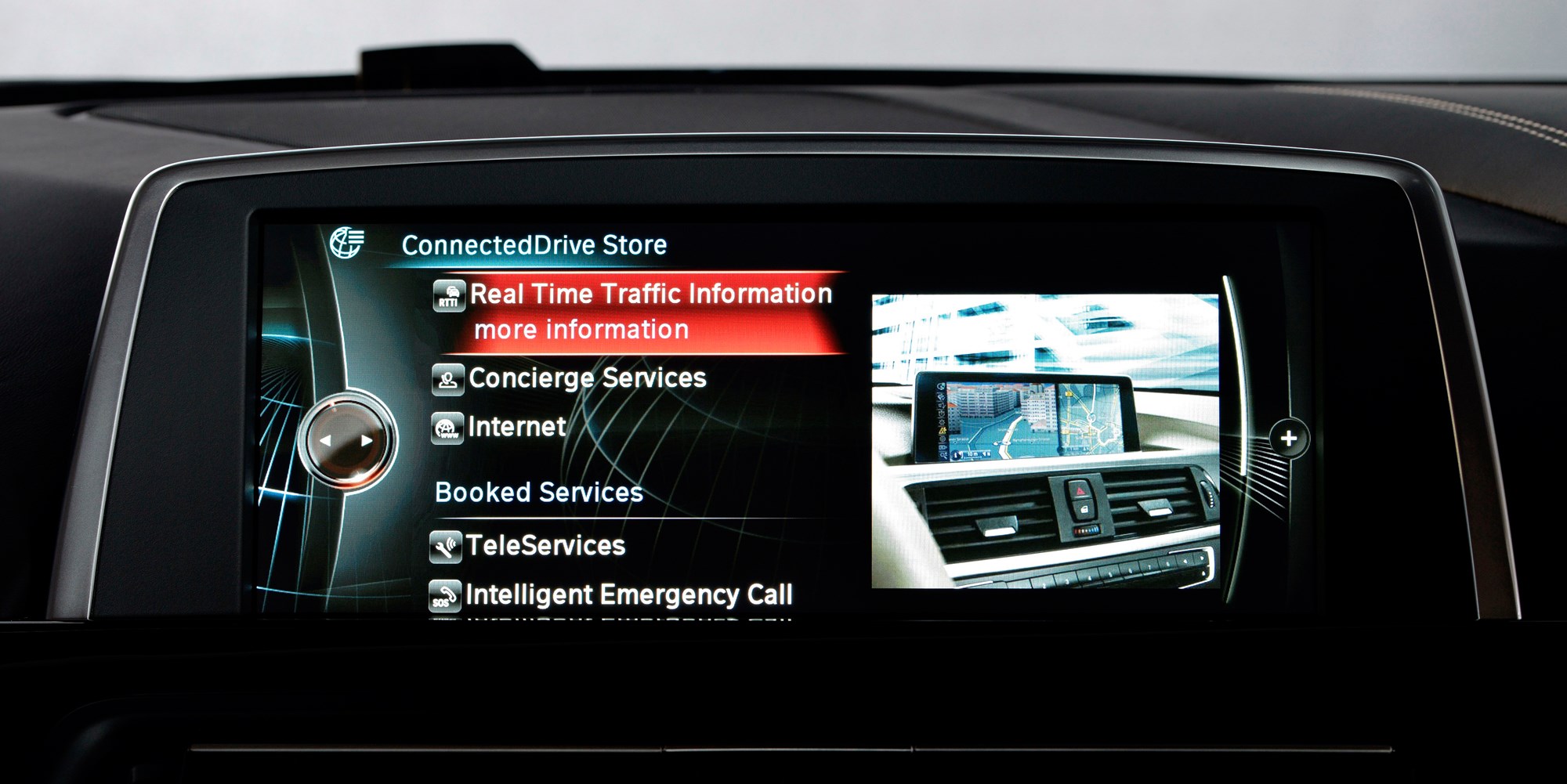

Now with the increasing prevalence of connected car technology — whereby a vehicle features an extra layer of communicative interactivity between its systems and the environment around it, such as a concierge service link to a call centre, real-time traffic information through the GPS system, or even a mobile Wi-Fi hotspot — cyber security experts believe the modern car’s computer network is ripe for hacking.

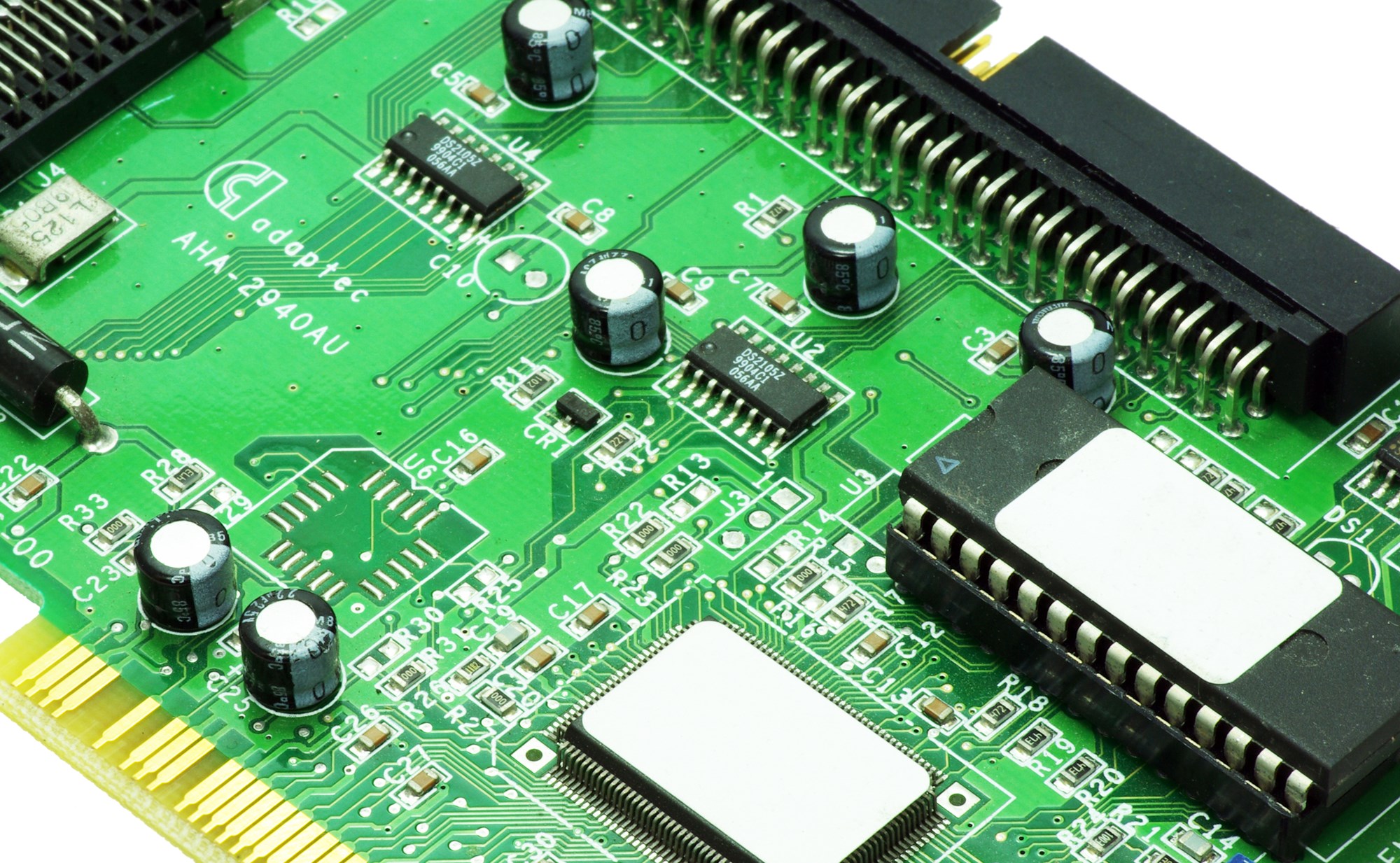

Defence layers need to be embedded into car technology at a development level (above)

After all, these systems are difficult to secure, feature multiple entry points and are well understood by hackers.

But wait a minute.

Hacking into cars? Is this really a thing?

In laboratory conditions, yes. As yet though, the industry hasn’t been hit by an attack on a car’s inboard computer systems.

“This is a relatively new area of security research and the environment we are dealing with is quite complex,” Bailey says.

“But I think the various manufacturers are starting to realise the gravity of the situation on how security is going to have a major impact on their business.

“As a result, we are starting to see some initiatives from various manufacturers, such as the introduction of the Automotive Cybersecurity Best Practices framework, as well as activities such as participating in bug bounties, where they encourage and reward security researchers to find vulnerabilities in their systems.”

To combat any potential threat of hack action, defence layers need to be embedded into in-car technology at a development level.

“Security should be right at the forefront of the design stage and should not be an afterthought,” Bailey says.

This could be especially relevant where the development of autonomous vehicles is concerned.

Where the passenger’s ability to override a vehicle’s control system might be compromised, such as in an autonomous ride-sharing scenario, the impact of a maliciously hacked system could be deadly. But don’t fret.

Your car isn’t about to drive off the road because some anonymous hacker in a basement told it to do so. At the moment, researchers are looking at much lower-impact threats, typically based — just like online scams — around user vulnerability rather than the system infrastructure.

Peter Bailey, general manager of Aura InfoSec

One of the first things hackers look for when attacking a system is the easiest way in. Once inside, the hacker can escalate his or her permissions or access until they get to the target system that they’re looking for.

I think the various manufacturers are starting to realise the gravity of the situation on how security is going to have a major impact on their business.

If a hacker is attempting to access someone’s bank account, the easiest thing to do is to compromise the person via their home computer and steal their password — often through malware disguised as genuine correspondence from a trusted source — rather than attacking an account via the user’s actual banking infrastructure.

Therefore, the weakest link in any network is the user. And surprisingly, cars are no different.

A research team recently managed to get a car to unlock itself by spoofing a cellphone station, which sent it a fake ‘unlock’ signal (a task that required months of work).

But perhaps an even easier way to compromise a car’s computer system would be via rooted firmware through updates that users might download from the manufacturer’s website and install themselves in the car using a USB stick.

And that is part of the security issue; the manufacturers themselves.

A car’s inbuilt computer system. Pictures / Supplied

With carmakers generally working to a five-year model development lifespan, Bailey points out there is often a distinct gulf between the speed with which in-car connected technology develops and the rapidity with which seasoned hackers could find weaknesses in that technology.

In other words; the tech we’re increasingly taking for granted is already hackable by the time it appears on the market.

“By all practical means, it will be hard, if not impossible, to create a 100 per cent secure product [for car companies].

“We have noticed the difference in response time taken by different manufacturers to issue patches for vulnerabilities in their vehicles.

“This is where an in-depth defence approach would be useful.

“Creating as many layers of defence while reducing exposed attack surface area would go a long way,” he says.